This is the ninth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

Everyone who has watched a movie that includes a criminal trial or a Congressional hearing knows about one aspect of the Fifth Amendment: the right not to incriminate yourself.

“No person . . . shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself,” reads the relevant clause of the amendment.

Alleged crime boss Tony Accardo took the Fifth Amendment more than 170 times during the 1951 Kefauver Hearings in the United States Senate, a dramatic event captured on live television.

But that important right is only one of five in the Fifth Amendment which guarantees individual liberties in civil and criminal trials and outlines “basic constitutional limits on police procedure,” the Cornell Law Institute notes.

Here’s how the full text of the Fifth Amendment reads:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown so you can identify those five constitutional limits on police procedures more readily:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime,

(1) unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger

(2) nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb (a concept known as double jeopardy)

(3) nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself

(4) nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law

(5) nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation (The government’s ability to take private property for public use with just compensation is known as eminent domain)

Grand Jury

A grand jury is different from a trial jury, which is what most people think of when they hear the word “jury.”

You are probably familiar with what a trial jury is: Twelve men or women who are “peers” of the accused who are empowered in a trial to determine whether or not the accused is guilty of the crime of which they are charged.

The accused is arrested by the police based on evidence that he or she has committed a crime. At the trial, which is presided over by a judge, the prosecuting attorney presents evidence for the jury that the accused, the defendant, is guilty of the crime, while the defense attorney argues that the evidence presented by the prosecuting attorney does not establish “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the defendant is guilty of the crime.

Once both the prosecuting attorney and defense attorney have presented their case, the judge provides the trial jury with instructions on the legal standards they should use in their deliberations. The jury then retires to complete their deliberations in private, and comes to a verdict: the defendant is either guilty or not guilty of the crime of which he or she is charged.

Unlike a trial jury, a grand jury plays a different role, but “not one that involves a finding of guilt or punishment of a party.”

“Instead, a prosecutor will work with a grand jury to decide whether to bring criminal charges or an indictment against a potential defendant — usually reserved for serious felonies. Grand jury members may be called for jury duty for months at a time, but need only appear in court for a few days out of every month. Regular court trial juries are usually 6 or 12 people, but in the federal system, a grand jury can be 16 to 23 people,” Findlaw.com notes:

While all states have provisions in their laws that allow for grand juries, roughly half of the states don’t use them. Courts often use preliminary hearings prior to criminal trials, instead of grand juries, which are adversarial in nature. As with grand juries, preliminary hearings are meant to determine whether there is enough evidence, or probable cause, to indict a criminal suspect.

Unlike a grand jury, a preliminary hearing is usually open to the public and involves lawyers and a judge (not so with grand juries, other than the prosecutor). Sometimes, a preliminary hearing proceeds a grand jury. One of the biggest differences between the two is the requirement that a defendant request a preliminary hearing, although the court may decline a request.

Grand jury proceedings are much more relaxed than normal court room proceedings. There is no judge present and frequently there are no lawyers except for the prosecutor. The prosecutor will explain the law to the jury and work with them to gather evidence and hear testimony. Under normal courtroom rules of evidence, exhibits and other testimony must adhere to strict rules before admission. However, a grand jury has broad power to see and hear almost anything they would like.

However, unlike the vast majority of trials, grand jury proceedings are kept in strict confidence.

Though independent entities, grand juries are heavily influenced by the prosecutors who convene them.

“In a bid to make prosecutors more accountable for their actions, Chief Judge [of the New York Court of Appeals] Sol Wachtler has proposed that the state scrap the grand jury system of bringing criminal indictments,” the New York Daily News reported on January 31, 1985.

“Wachtler, who became the state’s top judge earlier this month, said district attorneys now have so much influence on grand juries that ‘by and large’ they could get them to ‘indict a ham sandwich,’ ” the News noted.

Not everyone agrees with Judge Wachtler, but it is rare for a grand jury to not return an indictment sought by the convening prosecutor.

Still, “[a] person being charged with a crime that warrants a grand jury has the right to challenge members of the grand juror for partiality or bias, but these challenges differ from peremptory challenges, which a defendant has when choosing a trial jury,” the Cornell Law Institute notes:

When a defendant makes a peremptory challenge, the judge must remove the juror without making any proof, but in the case of a grand juror challenge, the challenger must establish the cause of the challenge by meeting the same burden of proof as the establishment of any other fact would require. Grand juries possess broad authority to investigate suspected crimes. They may not, however, conduct “fishing expeditions” or hire individuals not already employed by the government to locate testimony or documents. Ultimately, grand juries may make a presentment. During a presentment the grand jury informs the court that they have a reasonable suspicion that the suspect committed a crime.

Double Jeopardy

Under the double jeopardy clause of the Fifth Amendment, you can not be charged for the same crime a second time if you have been given a fair trial and found not guilty of those charges. It is designed to prevent prosecutorial abuses by the government.

“The government must place a defendant ‘in jeopardy’ for the Fifth Amendment clause to apply. The simple filing of criminal charges doesn’t cause jeopardy to “attach”—the proceedings must get to a further stage,” according to the Nolo.com legal encyclopedia.

“Generally, jeopardy attaches when the court swears in the jury. In a trial before a judge, jeopardy attaches after the first witness takes the oath and begins to testify,” Nolo.com states.

“The Double Jeopardy Clause aims to protect against the harassment of an individual through successive prosecutions of the same alleged act, to ensure the significance of an acquittal, and to prevent the state from putting the defendant through the emotional, psychological, physical, and financial troubles that would accompany multiple trials for the same alleged offense,” the Cornell Law Institute notes:

Courts have interpreted the Double Jeopardy Clause as accomplishing these goals by providing the following three distinct rights: a guarantee that a defendant will not face a second prosecution after an acquittal, a guarantee that a defendant will not face a second prosecution after a conviction, and a guarantee that a defendant will not receive multiple punishments for the same offense. Courts, however, have not interpreted the Double Jeopardy Clause as either prohibiting the state from seeking review of a sentence or restricting a sentence’s length on rehearing after a defendant’s successful appeal.

Self-Incrimination

“The Fifth Amendment protects criminal defendants from having to testify if they may incriminate themselves through the testimony. A witness may ‘plead the Fifth’ and not answer if the witness believes answering the question may be self-incriminatory,” the Cornell Law Institute notes:

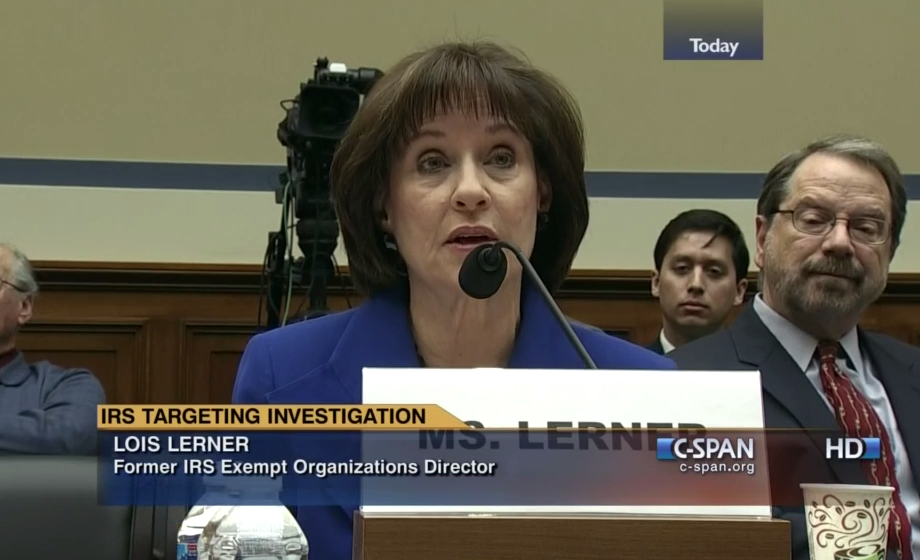

The Fifth Amendment’s protection against self incrimination can also be invoked by witnesses called to testify before Congress. Such was the case in 2013 when IRS attorney Lois Lerner invoked her Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination when she appeared before a committee of the House of Representatives and refused to answer any questions. She subsequently resigned from the IRS after allegations were made that she unlawfully targeted conservative Tea Party groups for scrutiny not applied to other groups. After her resignation, she appeared before the same committee in 2014 and again invoked her Fifth Amendment rights and refused to testify before the committee.

In recent history, the Supreme Court has extended the right of self-incrimination to the very beginning of the criminal proceedings process.

“In the landmark Miranda v. Arizona ruling, the United States Supreme Court extended the Fifth Amendment protections to encompass any situation outside of the courtroom that involves the curtailment of personal freedom. 384 U.S. 436 (1966),” the Cornell Law Institute reports:

Therefore, any time that law enforcement takes a suspect into custody, law enforcement must make the suspect aware of all rights. Known as Miranda rights, these rights include the right to remain silent, the right to have an attorney present during questioning, and the right to have a government-appointed attorney if the suspect cannot afford one.

If law enforcement fails to honor these safeguards, courts will often suppress any statements by the suspect as violative of the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination, provided that the suspect has not actually waived the rights. An actual waiver occurs when a suspect has made the waiver knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily. To determine if a knowing, intelligent and voluntary waiver has occurred, a court will examine the totality of the circumstances, which considers all pertinent circumstances and events. If a suspect makes a spontaneous statement while in custody prior to being made aware of the Miranda rights, law enforcement can use the statement against the suspect, provided that police interrogation did not prompt the statement.

Due Process

Due process means that everyone in the United States is entitled to a fair trial.

In other countries where this right is not guaranteed, trials are some times not fair. This trials, known as “show trials” or “kangaroo courts,” where the guilty verdicts are determined before the trial even begins, are conducted for purposes of propaganda to advance the government’s objectives, rather than justice for the accused.

“The guarantee of due process for all persons requires the government to respect all rights, guarantees, and protections afforded by the U.S. Constitution and all applicable statutes before the government can deprive any person of life, liberty, or property,” the Cornell Law Institute notes:

Due process essentially guarantees that a party will receive a fundamentally fair, orderly, and just judicial proceeding. While the Fifth Amendment only applies to the federal government, the identical text in the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly applies this due process requirement to the states as well.

Courts have come to recognize that two aspects of due process exist: procedural due process and substantive due process. Procedural due process aims to ensure fundamental fairness by guaranteeing a party the right to be heard, ensuring that the parties receive proper notification throughout the litigation, and ensures that the adjudicating court has the appropriate jurisdiction to render a judgment. Meanwhile, substantive due process has developed during the 20th century as protecting those right so fundamental as to be “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.”

Just Compensation

“While the federal government has a constitutional right to ‘take’ private property for public use, the Fifth Amendment’s Just Compensation Clause requires the government to pay just compensation, interpreted as market value, to the owner of the property,” the Cornell Law Institute notes.

“The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly grant condemnation powers to the federal government. Such power is generally inferred today from clauses of Article 1, Section 8, that give Congress authority to establish post offices and post roads as well as authority over property obtained for forts, arsenals, and other similar facilities, and from the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment,” Professor Bruce Benson of Florida State wrote in 2004.

The clauses of Article 1 appear to limit federal takings by requiring the “consent of the legislature of the state” in which the property is located. This constraint raised the cost of federal seizures somewhat (the states faced no such constraint) and limited their use until the Supreme Court eliminated the constraint in Kohl v. United States (91 U.S. 367 [1875]), in which the federal government was determined to have the power to take property directly in its own name. Before this case (which arose because Congress authorized the secretary of the Treasury to acquire land in Cincinnati for a public building, and federal officials condemned the land directly rather than obtaining it through state condemnation or voluntary exchange), the federal government had condemned land only through the intermediary of the state government.

“James Madison, who wrote the Fifth Amendment, hoped to restrict the takings that had been made in the colonies under British rule and in the new states after the revolution because he wished to make individual property rights more secure, but he did not go as far as Jefferson would have liked, perhaps as a compromise to garner sufficient support for the Constitution. He chose instead to require compensation explicitly, and he used the term public use rather than public purpose, interest, benefit, or some other term in an effort to establish a narrower and more objective requirement than such alternative terms might require,” Benson wrote.

“The U.S. Supreme Court has defined fair market value as the most probable price that a willing but unpressured buyer, fully knowledgeable of both the property’s good and bad attributes, would pay. The government does not have to pay a property owner’s attorney’s fees, however, unless a statute so provides,” the Cornell Law Institute notes.

In Kelo v. City of New London, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered a controversial opinion in which they held that a city could constitutionally seize private property for private commercial development. 545 U.S. 469 (2005).

Suzette Kelo, a nurse who owned “a little pink house” in New London, Connecticut was forced to sell it to the city of New London against her wishes based on that decision.

She wrote a book about her case, which was recently made into a movie. You can watch a clip of that movie here:

“The Supreme Court’s 2005 ruling in Kelo v. New London was that year’s blockbuster. Literally. The Court gave its blessing to the use of eminent domain to destroy blocks of housing so that city officials could pursue their dreams of a more wondrous community by seizing private property for a planned commercial development,” George Leef wrote at Forbes Magazine recently:

That taking had been challenged on the grounds that the precise wording of the Fifth Amendment’s provision allowing eminent domain – that the property had to be taken for “public use” – did not countenance takings where there was merely a purported “public purpose” in doing so. The Court’s “liberal” wing didn’t care either about the Constitution’s precise words or the harm its ruling would inflict on lots of “little guy” owners whose modest properties stood in the way of grandiose political projects.

Kelo is among the many cases demonstrating that ordinary Americans are served best by the strict rule of law rather than by “progressive” jurisprudence that empowers government officials.

And that is the message strongly conveyed by the recently released movie about Susette Kelo’s fight with the arrogant officials in New London, CT. Little Pink House premiered February 2 at the Santa Barbara film festival. In the film, Catherine Keener (who was nominated for an Oscar for her roles in Being John Malkovich and Capote) portrays Susette Kelo, the nurse who refused to meekly accept the city’s decision to force her out of the small home she had fixed up and loved. A clip from the film is available here.

“In the end,” Leef concluded, “the homes belonging to Susette Kelo and her neighbors were demolished for no purpose at all, since the hoped-for development collapsed. What was once a nice residential area is now acres of rubble. Perhaps some viewers will get the message that big government plans are prone to turning into boondoggles. Perhaps some others will get the point that it’s morally wrong for government officials to treat property owners as pawns on a chessboard, easily exchanged for a positional advantage in the game.”

[…] was tried in a federal court. Therefore, our analysis is based on the due process clause of the fifth amendment, which contains an equal protection component. Bolling v. Sharpe, 1954, 347 U.S. 497, 498-500, 74 […]